- September 23, 2016

- Posted by: SportsV

- Categories: Features, Home News, Interviews, News

Randy (Rand) Shear, Lead Design/Manager/Sports & Entertainment at RandShearDesign LLC, shares his thoughts on the rise and ultimately the fall of donut (doughnut) stadiums.

“You can tear down the structure but you can never tear down how you feel about it’s memories” – Bea, wife of Dahlen K. Ritchey, architect (Three Rivers Stadium)

Designing the Impossible

Stadium design has always looked to the future for its inspiration. Long before the term ‘hybrid’ came into fashion describing automobiles, stadiums in the late 50’s were dreamed and imagined as a precursor to ‘stadia hybrids’. Stadium design was based on the principles associated with modernist architecture and industrial design in the 20th-century ‘form follows function’. In this case, economics over sports drove the designs and the ‘multi-purpose orbicular stadium’ was born.

Between 1961 and 1976, fifteen new multi-purpose stadiums were built: some domed, most all circular wheels of concrete, hence these stadiums were also referred to as ‘concrete doughnuts’. Maligned by the fans, players and architects alike, these new ‘stadia’ were doomed from the start and for the numerous stadium designers and architects they were truly ‘designing the impossible’.

The Rise and Fall of the ‘Concrete Doughnuts’

With just a couple of these dual-use ‘concrete doughnuts’ still standing, we can begin to reflect back on why these stadiums came about in the first place. Did they represent a modern ‘ballpark’ to play the national pastime in? Definitely not! Were they wonderful monumental ‘stadia’ built for the American gridiron game? Not really! So why were they so popular to build?

There are many theories on the rise and fall of these stadiums. Some claim it was the two-team revenue split, others felt the lack of sponsorship like signage was the cause, and then the purist fans who hated them for multiple reasons. Stark, impersonal and indistinguishable from each other, they were later derisively called “Cookie Cutter” stadiums-with hardly a personality of their own or having odd quirky features of older ballparks. These multi-purpose facilities quickly became the norm, playing host to football and baseball teams in countless cities, including Cleveland, Washington DC, New York, San Diego, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Oakland, San Francisco, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and Seattle.

But these stadiums were deeply flawed mainly for the ‘fan experience’, as concepts, these ‘in vogue’ stadiums from a construction cost perspective were great, at a time when there was rapidly escalating labour costs, owners felt compelled to build one stadium for two sports. But from a sports design perspective, baseball was a particular target of scorn from baseball purists, largely because some of these stadiums had no lower-deck seats in the outfield being close to any action on the field was impossible, simply put; baseball has diamond-shaped field and football a rectangle field, like ‘da’ – each of these dual sports arrangements tragically compromised each other. In most cases, the conversion from one sport to another, which occurred 20 times a year, cost 10’s of thousand of dollars, even the pitcher’s mound magically sank away out of sight on hydraulic lifts 3ft below the field turf. And don’t even get me started about the low attendance of less than quarter of full capacity for baseball, with the upper deck seats empty.

The Sixties

This was a great decade, sometimes referred to as the ‘cultural decade’, the 1960’s were exciting times, no doubt. It was the tail end of the ‘Atomic Age’ of industrial design, a time of the space race and astronauts landing on the moon. Technological leaps and engineering marvels occurred frequently. ‘The times they are a changin’ a song by Bob Dylan was popular. Design, fashion, and culture were leaping forward, it was Jet-Set, the Jet-Age and the Jetsons, the Wham-O’s Hula Hoop was the huge craze, bell bottoms and mini skirts were the latest fashions and ‘pop culture’ was hitting its stride.

It was only logical stadium design had fallen in line with that mid-century modern movement. For the first time, stadiums went beyond sports and hosted concerts. When John, Paul, Ringo and George (aka The Beatles) arrived in America for the first time, the ‘Fab Four’ helicoptered in and Brinks trucked out of Flushing Meadows to perform at Shea Stadium; euphoria and mass hysteria followed; and Beatlemania was born in a multi-functional stadium.

Fan experience vs. Team Branding

It would not be for another 30 years before naming rights and corporate identity became commonplace. But sports venue sponsorship for stadiums and ballparks was nothing new; in 1912 Fenway Park in Boston was named after the ‘Fenway Realty’ company, and it became more widely accepted when, in 1926, William Wrigley, owner of the Chicago Cubs, named his stadium Wrigley Field.

In 1953, Anheuser-Busch head and St. Louis Cardinals owner, August Busch Jr., proposed renaming Sportsman’s Park, occupied by the Cardinals, ‘Budweiser Stadium’. When this idea was rejected by Ford Frick, the then Commissioner of Baseball, Anheuser-Busch proposed the title ‘Busch Stadium‘ after one of the company’s founders. The name was readily approved, and Anheuser-Busch subsequently released a new product called ‘Busch Bavarian Beer’. The name would later be shifted to the Busch Memorial Stadium in 1966, but shortened back to Busch Stadium in the ’70s, as it remained until the stadium closed in 2005.

Selling the naming rights to an already-existing venue had been notably less successful, as in the attempt to rename Candlestick Park in San Francisco to 3Com Park. However, corporate sponsorship and naming rights really became popular after the ‘doughnut stadium’ was replaced in the 90’s due to the addition of special club sections, corporate luxury suites, and with that came multi-million dollar naming rights had a local business connection, but never an owner’s name.

Lakefront Stadium: The prototype

Lakefront Stadium later known as the Cleveland Municipal Stadium or known to some as the ‘mistake by the lake’ was truly the predecessor stadium for all the ‘doughnut’ stadiums to follow. The impetus for Cleveland Municipal Stadium, which opened in 1931, came about from the city manager and team owners, who felt a new stadium would benefit both commerce and real estate values in downtown Cleveland. It was later rumoured that the stadium was conceived as part of the bid to host the 1932 Olympic Summer Olympic Games, which subsequently went to Los Angeles. It also was the first stadium built with public monies. Lakefront Stadium had a capacity of 78,189. It consisted of a covered double-decked grandstand that extended from behind home plate, down and around the foul poles to an uncovered section of bleachers in the outfield. Oddly, the field dimensions were a short down the base lines (322ft) and huge down centre field (a whopping 463ft). Even though the stadium shape was an acorn-horseshoe and not a pure circle, the stadium was host to both baseball and football and, for that reason, this stadium was the first of its kind well before the truly first multi-purpose stadium was even accomplished.

RFK is the 1st

Located approximately 2.2 miles due east of the US nation’s Capital, RFK-Robert F. Kennedy Stadium was the first of the true ‘doughnuts’ to be built, and the last to be closed, at least for baseball and football; Major League Soccer (MLS) is still played there today by the D.C. United team. Built in 1960 this undulating concrete structure had a distinctive wavy roof was designed by Dallas Architect, George Leighton Dahl, and Osborne Engineering (also 3 Rivers Stadium).

The stadium had hosted a few teams, the Washington Redskins (1961-1996) football team and the Washington Senators (1962-1971) baseball team, then later the Nationals baseball team (2005-2007).

RFK still stands as one of the last of the great doughnut stadiums in the country, but still most MLS games only require approximately 44% less seats than the existing stadium, and once the professional soccer team is able build a customized standalone stadium, this will leave the great RFK vulnerable to demolition.

In 2016, Dutch ‘Starchitect’ Rem Koolhaas and his firm, OMA, was hired to study the site and produced two master plans and phased designed concepts. According to OMA, these were aimed at “leverage the District’s waterfront, provided neighborhood serving amenities and connect the current site with increased and sustainable green space, flexible recreational fields and pedestrian-friendly pathways”, but at the same time never offered any re-purpose solutions.

Riverfront-Cinergy Field

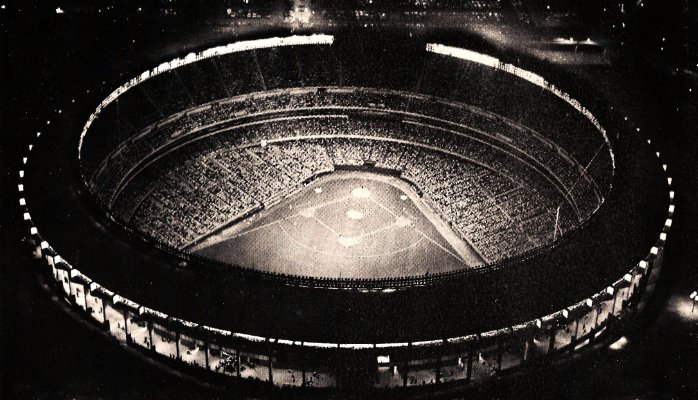

The Riverfront Stadium came into being on edge of the Ohio river on a June day in Cincinnati in 1970 when a helicopter delivered the home plate from the historic Crosley Field Ballpark. At the same time, famed coach Mr. Paul Brown was granted a football franchise for the Bengals team, who were be a part of the NFL once the AFL leagues merged in the same year. It had been decided that the baseball and football team would share a facilities for ironically budgetary reasons. The plans for the stadium could be traced back to masterplans done by the architect Heery and Heery (FABRAP) of Atlanta Georgia, which placed the circular-paddleboat-wheel like cylinder atop a multi level parking square platter, that plunked itself at the Ohio River’s edge and connected it to the city’s downtown with shed like pedestrian bridges reaching out over the Fort Washington highway. The design really had little or none urbanistic sensitivities of today’s standards. The stadium however was one of the first to introduce a SonyJumboTron video screen and with that came the infamous ‘Kiss-Cam’, later on the screen was replaced with a more technological visible and less expensive LED screen.

Later, in 1996, Cinergy Corporation captured the naming rights and re-named the stadium which dominated the Ohio river’s edge for 32 years until the televised implosion on a cold December day after the Great American Ballpark which, sat only several feet away, in a Siamese-twin state was almost finished for the next season.

Multiple historical moments happened in those three decades, too numerous to mention, but over the years, fans never really had an affection for the stadium, like they did for Crosley Field. Even when we were designing Great American Ballpark at HOK Sport (GAB), during the public meetings with the fans, they always asked us to design the new ballpark with features of the old Crosley Field, like the infamous sloped terraces and absolutely no features from the Cinergy Field, even the steep upper deck was maxed out at 36 degrees and was not worthy repeating. In order to fit the new ballpark in place a section between expansion joints of the Cinergy Field was removed, a huge 40ft wall was added to the batter’s eye, known as ‘the black monster’ no relation to the ‘green monster’. A local ‘baseball’ reporter, stated that the ballpark in it deconstructed state, actually gave the old stadium some character and in an urbanistic contextual way opened up the old homogeneous boring circular stadium-with grand views out towards the Ohio River, the bridges and Mt. Adams.

Life’s a Journey – ‘Enjoy the ride’

At my arrival to the HOK Sport offices, housed in an old renovated garment warehouse building in downtown Kansas City in 1996, I had toured the office on my first day, and when I asked what project I might be working on, I was told “I think you will be workin’ on a ballpark in San Francisco”, I quick repeated “Sorry; did you say Ballpark and San Francisco in the same sentence?”.

It was true, Pac Bell Park was a new project on the boards and it was very exciting to be what seemed to be, in the right place at the right time. This office for HOK had concentrated on sports since 1983 and the office expanded to close to 200 people when I arrived.

At the same time, the Nissan multi-million dollar commercial with ‘you really got me going’ song by Van Halen, ‘Life’s a journey-enjoy the ride’ ad aired at the 1996 Superbowl XXX. The highly rated and multi-million-dollar campaign showed a Toy Story-esque ad for the Nissan 300ZX Turbo car and for me the commercial was an analogy for time. The time when the multi-use stadiums were being demo’d and, consequently then opened the door for each city to have new stadiums built for American baseball and football. Enjoy the ride were the few decades which followed of sport facilities being designed one after the other.

Astroturf is Invented

In tangent with these great monumental stadiums, seemingly futuristic and modern, a new concept had emerged, ‘artificial turf’, which would replace natural turf or what everyone refers to as grass. This was mostly developed due to the different field arrangement modifications done between football and baseball.

This ‘artificial turf’ was originally conceived by a textile designer professor, Dean David Chaney, in 1960, the turf was further patented in 1965 by Donald L. Elbert, James M. Faria and Robert T. Wright, who worked at Monsanto, originally patented as ChemGrass and was later re-branded as AstroTurf after its highly publicised application in the state-of-the-art indoor Astrodome in Houston.

Technically speaking, this first-generation turf was comprised of synthetic fibres made to look like natural grass, it was more like plastic carpets directly applied directly to a concrete base. The 1970 World Series was the first time a major league game was played on AstroTurf (previously installed at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium), as the Reds played the Baltimore Orioles – the Orioles won by the way.

While working at HOK Sport on the design of The Great American Ballpark in Cincinnati, which was designed with natural turf (we actually surveyed the fans), we interviewed Pete Rose for a video about the new ballpark and asked him some questions about the re-introduction of natural grass, but ‘the hit king’ kept answering the questions with his long-winded praise for how great the ball bounced off the AstroTurf at Cinergy Field, later on Johnny Bench exalted the virtues of natural turf for baseball.

A real Park where ‘B’ ball is played

The retro-stadium trend, began with redesign of Oriole Park at Camden Yards. In 1984, the Baltimore Colts moved to Indianapolis, in part because Baltimore and Maryland officials refused to commit money for a replacement for Memorial Stadium. Not wanting to chance losing the Orioles — and Baltimore’s status as a major-league city in its own right — city and state officials immediately set about building a new park in order to keep the ball-team in town.

In 1992, Oriole Park at Camden Yards, designed by HOK Sport, was a new day in sports architecture. Specifically designed to generate more profits, with a club and suites, and at the same time, have a retro-bricky-feel-snugged up adjacent to the old B&O warehouse building giving up Eutaw Street to pedestrians. Owners and fan alike loved it…

Need for capital to build bigger and better ballparks brought new sponsorship, ads, TV rights and eventually custom-designed corporate suites and clubs, and even special corporate zones – the profits those now ballgames generated, these were real ‘Ballparks’ with a capital ‘B’- strongly contextual, fan-centric facilities-designed specifically for our ‘national pastime-baseball only’! The writing was on the wall. Soon, other major league teams followed the trend and held cities hostage, threatening to leave without new separate facilities. In turn, this movement brought with it, the eradication-demolition-implosion of every one of these boring ‘concrete circles’ that no one wanted and dotted our biggest cities.

Only one ‘doughnut’ now remains in these, the United States, and that’s the Oakland Coliseum, which still welcomes two major league team sports, the Oakland Athletics and Oakland Raiders. Over the years, many proposals have been made for both baseball and football. But this too will end someday – as Bea said, “just good memories will be left”.

Author’s credits: Randy (Rand) Shear is Lead Design/Manager/Sports & Entertainment at RandShearDesign LLC. Rand first published this article on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/romancing-donut-stadiums-randy-rand-shear?trk=eml-b2_content_ecosystem_digest-network_publishes-123-null&midToken=AQGMQKh8jpcFCQ&fromEmail=fromEmail&ut=1K9hMYQcdm17s1

Image: Opening Night at Riverfront Stadium. Credit: www.oldtimecincy.com